Taking Marriage Class at Guantánamo

While imprisoned for 14 years, a young Yemeni man learns about love from a fellow detainee — and an iguana.

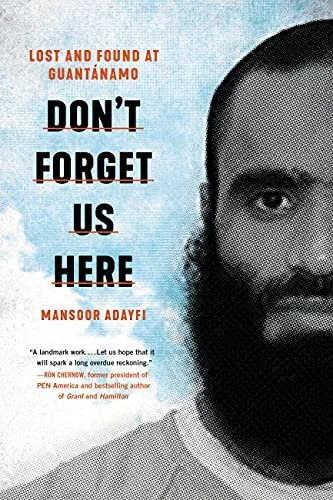

Illustration by Brian Rea

New York Times, Modern Love

By Mansoor Adayfi

July 27, 2018

Until I was 35, the most significant relationship I’d had as an adult was with an iguana.

It wasn’t easy to meet anyone where I was for all of my 20s and nearly half of my 30s, at the prison camp at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba. After I arrived, I was put in an isolation cell, where huge fans outside of each cell ran day and night, making deafening noise to prevent us from talking to each other.

Even when we went outside for recreation, we were not allowed to talk to the other detainees. But outside we did meet new friends: the cats, banana rats, tiny birds and iguanas that came through the fences, asking to share our meals.

I had a good friendship with beautiful young lady, an iguana. She was so elegant. She used to come every day at the same time, and we would have lunch together. When I went on a hunger strike, I had no food to give her, and I was ashamed to stand there without food as she came up to me. Sometimes the guards punished us for sharing our meals with the animals, but they couldn’t stop me from talking to her.

She couldn’t talk back, but she was a good listener. As the years passed, our friendship grew into a strong bond.

Finally, after seven years of isolation, I was moved into a communal block where I could talk with my fellow detainees. I was born in a tiny village in the mountains of Yemen and was only 19 when I came to Guantánamo. I didn’t know much about the world; the world to me was my village. Now, my world was Guantánamo.

Until I was 12, I thought I had been born from my mother’s knee. I learned in school where babies really came from, but there was no dating in my society, so my knowledge remained theoretical. The same was true for most of us. Very few of us had been married or knew much about the relations between men and women.

Even so, talking about women was our favorite topic. Not in a bad way; as Muslims we are forbidden to talk about women in a bad way. But we talked about women because it relaxed us. When someone would tell a story about a woman, we all would listen. While being surrounded by men we imagined loving women.

We weren’t the only ones who missed women; the male guards did, too. There were very few female guards.

One of the older, married detainees saw that the single detainees were desperate to know about women, so he decided to teach us. We used to arrange classes and learn from each other anything that could be taught.

For example, a former chef taught a cooking class. He would say, “Now, I will add the onion to the hot oil — shhhh shhhh,” imitating the sound of frying onions because of course we had no onions or oil or stoves. He would make jokes, asking the students to please taste the dishes to test if they had enough salt or if they thought the meat was ready, even though there was no salt or meat.

I didn’t like that class. It just made me hungrier.

On our first day of marriage class, our teacher began by asking us each to say what we thought about how men should treat women. We agreed that men should have absolute respect for women, but many of the students said men always were, and always would be, superior to women.

Then the teacher asked: “If you were a woman, how would you answer my question? How would you want men to treat you?”

At first we started laughing, imagining each other as women.

“Look at Mansoor with hair all over his body,” one detainee shouted at me. “You would scare all of the men.”

“If I were a woman,” another said, “I would make you all dream, cry and spend all of your money — but none of your ugly faces would touch a single hair of mine.”

Our teacher let us joke for a while but then said, “Answer my question, ladies!”

I said that if I were going to choose someone to accompany me for the rest of my life, I would want a wife who was better than me.

One of the students tried to embarrass me by saying, “So will you let your wife be in charge? Should men just be like donkeys, serving women?”

I argued that men have been thought to be superior throughout history, but look where we are now. War follows war without end. Men never give birth to a single soul. They only take lives.

I said that all of us, guilty or innocent, were sitting around Guantánamo talking about marriage instead of experiencing it because of what men had done. I finished by pointing out that we all knew that when there was a female commander in charge of our guards, we lived more peaceful lives. When the commander was a man, we were more likely to be treated badly.

“Mansoor is biased toward women,” one detainee said with a laugh.

“If I were a woman,” another said, “I would marry you!”

As we kept meeting for marriage class, our teacher taught us about loving and being loved. He described what it would feel like when we saw and talked to the woman we loved. He told us how we would act on our engagement day.

And then we had an entire class dedicated to the biggest day in our lives, the marriage day. We pretended that one of the students was getting married, and we held a traditional Yemeni wedding celebration. We sang and danced as if it were a real marriage.

I have never been in love, but now I could feel its sweetness. Just like the cooking class, the marriage class made me hungrier. I regretted not being married before I came to Guantánamo. I felt there was a missing part of myself, and that part was a wife and family.

For a while I had in my cell a photo from a friend of his 10-year-old daughter. I made a frame out of scraps of cardboard with flowers surrounding it and hung the photo on the wall. Whenever visitors came into my cell, I would tell them she was my daughter.

When they looked surprised that I had a blond daughter and started asking more questions about the mother, I would say I had never met her, but still, I had a daughter just the same. I gave her an Arabic name, Amel, which means Hope.

One night the guards came in and pepper sprayed us and tore down everything in our cells. They threw away my Hope.

I could have stopped going to the marriage classes. I could have stopped dreaming about love. But the only thing harder than living a life without love is living a life without pain. Pain tells us we are alive. That we can still feel. Sometimes, pain is like love. Because I could imagine love, even without my photo, I still had hope.

When, after many years of not being able to speak to my family, I was allowed phone calls with them, there was talk of perhaps trying to arrange a marriage for me, and I was tempted to accept this hope. But in marriage class, we had discussed the problem of forced marriage in some countries. The idea of girls being sold like sheep hurt me. And so I declined the possibility of such an arrangement.

Read the complete story at The New York Times